Chapter One

DARKWALL

LIGHT AND DARKNESS, ever expanding toward and contracting away, one from the other, unfolding and enfolding―thus are the shadows of heaven partnered in timeless dance.

Ages have passed since the beloved Sea Kings of Ein, brothers Asmund and Harek, were slain by the Shadowkind. Many years have been spent in the tyranny of fear and darkness, death, war, persecution, and evil; alas, too much evil. Yet the realm of Moirai was bright once, so much so that the royal brothers deemed it the Homeland of the Spirit and with a munificent creed known as Kings’ Law, they beseeched all to live in harmony with its wonders and enchantments. Perhaps it is only fitting, therefore, that the tempestuous gales sweeping off the Boreal Seas, akin to those that filled the sails of the Einish dragon ships and led the Sea Kings to discover this world so long ago, begin the telling of this tale.

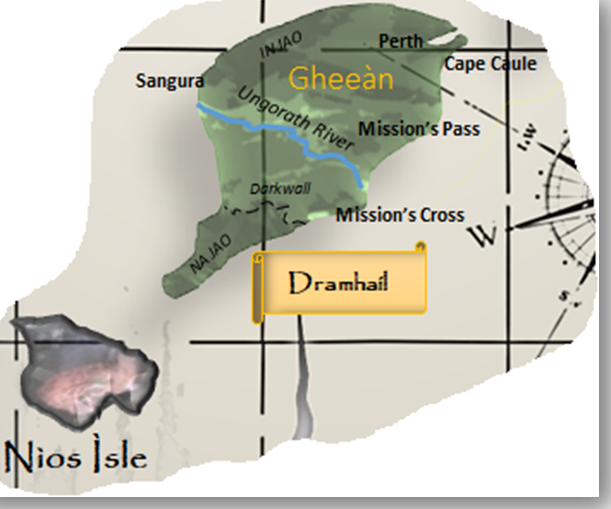

Driven by these gales from the northwest and countered by the atmospheric eddy of volcanic Nios Isle to the south, a cathedral of clouds amassed above the rainforest of southern Dramhail. The cumuli gathered and swirled through the mountains. Torrents of wind-driven rain, brief but severe, pummeled the soaring peaks and crests and crashed across ledges of dark layered rock, rushing down the steep slopes toward the jungle.

On a ridge in the eastern foothills bordering this mountain range, where the deluges diminished and frayed into gossamer veils, a lone figure stood and stared at the vast labyrinth of winding chasms below. The sprawling panorama abounded with canyons and gorges and valleys of tangled forestland, shrouded in ghostly mists.

The last of the midday storms lifted and vanished into the cerulean sky, and the man stepped from the shelter of the cliffs into cloud-dappled sunlight. Tall and broad shouldered, he was dressed in armored leathers and carried a great sword in a scabbard across his back. His hair was long and dark, and slivers of refracted light flashed from one eyehole of the mask covering his face. The tribes knew he was there. He knew they knew.

He sought passage into the heart of darkness. The cave that served as his shelter was small and well concealed and he had been there a long time, perhaps longer than he realized. He wanted to see for himself what few men had ever seen―the shadowy world beyond Darkwall, the forbidden Na Jao jungle. It was an instinctive quest, the reason he had been compelled to journey here from Saorsa after the Great Uprising had ended. He had discovered something very important in quelling that conflict with the emboldened Horks and Trolls. Now, passing through the ancient boundary was the purpose that drove him, and he was very close.

He sought passage into the heart of darkness. The cave that served as his shelter was small and well concealed and he had been there a long time, perhaps longer than he realized. He wanted to see for himself what few men had ever seen―the shadowy world beyond Darkwall, the forbidden Na Jao jungle. It was an instinctive quest, the reason he had been compelled to journey here from Saorsa after the Great Uprising had ended. He had discovered something very important in quelling that conflict with the emboldened Horks and Trolls. Now, passing through the ancient boundary was the purpose that drove him, and he was very close.

Yet he was lost all the same.

Not for the first time, he knelt down and studied his reflection in the pooled water of the mountain brook near his cave. As always, the mask stared back at him, the ambiguous and expressionless veil of woven fabric that rendered his disfigured aspect palatable; and the witch-eye, the marvel of consecrated crystal that granted his remarkable vision, glistening with shards of prismatic light. Alongside this stark image were the afternoon clouds, whorl-patterned tufts rushing the somber mood of the heavens across the sky, reflecting upon the rippled surface. The day was choked with sorrows, like all the other days here at the threshold of the boundary.

Drink the mineral waters, Elandon, revive yourself.

The elemental spirits, earth, wind, water, fire, and yes, even sky―that which he once commanded in a tenuous yet powerful way, all spoke to him. Even the Ceann, the Gods of the One Dream, had once beckoned to him; for many years ago they had sent their emissaries, the Fánaí, who had bestowed him with otherworldly offerings. Yet such wonders did not ease his unrelenting torment. His innate gift of the Second Sight was more acute now than ever; yet it had become a haunting source of self-doubt, a way in which he clearly saw his failings, and how they might have been overcome.

Somewhere deep within, Elandon realized his suffering inhibited these natural forces. Perhaps he strove too hard, overreached himself, tried doing too much; yet what had best served to allay his angst for the better part of two decades was slaying Horks and Trolls and bleeding their husks, which he accomplished with uncanny dispassion and efficiency. Indeed, his feats had become legend across the Lar Isles.

You are the champion of black blood!

“I am the champion of death,” he retorted, mocking the spirits and the Gods and muting the voice within. The raven that visited each day cawed scornfully, as it pecked in the thornberry thicket outside the cave mouth behind him.

They said Elandon slew thousands with his gleaming sword; that the black blood of the Shadowkind ran upon the land, that the rivers flowed with stinking husks and the skies darkened with the wings of birds flocking to feast upon the battlefields; that the wretched stench of cremation pyres smoldered in his wake.

“Tell me, wise raven,” he said, standing and turning toward his winged friend, “what is to be gained here in the desolation of the jungle, hearing only my own voice amongst the solemn sighs of the wind? Perhaps I am not meant to find passage into the Na Jao?”

Although he had offered such words to his companion before, he was more disconsolate on this day. His frustration was mounting and the thought of turning back was unbearable. A desperate restlessness and sense of urgency suddenly charged the moment, and Elandon felt a distinct change stirring in the wind.

The raven abruptly spread its wings and flew away. A precipitous silence ensued, followed by a strong scent similar to the musky odor of rotting wood, announcing the arrival of another presence. Elandon stilled himself as he heard a heavy scuttling among the rocks above, then a great shadow, a brown hulking shape, emerged from a crag in the cliffs and issued a deafening roar.

A bear he thought, taking a few backward steps and contemplating his escape. What leaped down before him, however, was a human figure that moved almost too quickly to believe; for a moment, Elandon thought he was imagining things. Then, as abruptly as it had come, the strong smell dissipated and standing before him was a Mischanter, a soul-catcher, one who possessed the innate sorcery of the jungle and traveled among the tribes as healer and guardian.

He greeted Elandon with his arms raised and his eyes closed. His eye-lids were tattooed in woad that captured the light like blue glass and his course hair was braided in tight loops. He wore the waist-cloth of the local tribes and his legs also bore tattoos―elaborate coiling blue serpents, while still more woad marked the dark skin of his torso in an intricate depiction of the sun, moon and stars. The soul-catcher conveyed a fierce aura of wisdom and authority.

“The Ungorath people have named you Topengorang,” he said, opening his eyes and smiling. “It means mask of the soul. That shall be what I call you.” He commanded the common speech flawlessly with only a hint of his native sing-song accenting the words. “I am Manuuwan. I have come to greet you.”

Although none of the natives had shown themselves, Elandon’s witch-eye had glimpsed the silent shadows of scouts in the surrounding tangle on several occasions. “Yes,” he sighed, “despite my stealth, the tribes are aware of my presence.”

Manuuwan laughed. “The jungle knows you are here, Topengorang. Besides, the rumor of your pursuit precedes you. I was visiting the people along the eastern banks of the river or I would have come sooner. But it is just as well, for I have something from Mission’s Cross for you to see. Gather your belongings and follow me.”

“Very well,” agreed Elandon, curious about what the Mischanter could have brought from the old mission. “But if you know why I am here, then you know I seek passage through the boundary. I have already wasted precious time.”

“Tell me, what do you hope to discover in the forbidden Na Jao?”

“In the Great Uprising,” Elandon replied, “the Horks and Trolls were led by a vicious warlord, a Troll called Vortigen. Yet when he was killed, it was as if the heart of the hordes had been cut out. They lost their mettle and dispersed, ending the conflict. It occurred to me then that I must come here and behold the forbidden world of the Shadowkind firsthand.”

“And perhaps run your legendary sword through the heart of darkness itself?” smiled Manuuwan.

“I would see if such a thing could be done.”

“Your instincts are keen. The Shadowkind are amassing in the Na Jao. There is another Troll warlord, one mightier and more malicious even than Vortigen. His name is Chenghist and he assembles a great force of evil.”

“Can you show me the way through the boundary?” asked Elandon.

“Very well,” nodded the Mischanter, “I will guide you. But you are not yet ready. In order to navigate the spells that bind Darkwall, it will be necessary to grasp certain elements of the sorcery involved. For you, this includes a better understanding of death.”

“I understand plenty about death,” Elandon retorted, wryly.

“You are bitter, Topengorang. You must set this aside and embrace the essential mystery. Come, I shall teach you.”

♦♦♦

Manuuwan did not look back. With his blowgun resting across his shoulders, he set an august pace along the stream beds and left it to Elandon to keep up. Journeying down through the dense canopy of the jungle, they were mostly hidden from the afternoon sun. Occasionally along the path where trees had fallen, sunlight pierced the thick cover and illuminated the flight of tiny effervescent birds and swarms of brilliantly colored butterflies. But mostly gloom pervaded the undergrowth, and choruses of croaking frogs resounded in the diffused light.

Later in the afternoon they came upon a copse of moss-laden trees, at the center of which stood a towering elder, its massive trunk hollowed by termites. The dead wood was covered with spongy fungus that emitted a hoary, glowing rime when the soul-catcher scraped it off and mashed it in his palms. He funneled several handfuls into a bamboo shoot and slipped it into the leather pouch strapped around his neck.

At various points along the way, Manuuwan gently imitated bird chirps and leopard growls and other wildlife sounds that Elandon recognized but could not identify. Finally, at the edge of the forest where the great trees fell away to dark shrubs, tall swaying grasses and swampy plains, they came to a halt. As the sun sank lower on the horizon, Manuuwan whistled an array of avian calls across the wetlands.

“People believe they are more powerful than the beasts,” he proclaimed, “because they possess weapons and fire. But this is arrogance. Animals are far greater. They are strong within themselves and require no such implements. A Mischanter knows this and learns from the animals, especially those which are his totems.”

Splinters of iridescent light issued from Elandon’s witch-eye. He was reminded of one of the offerings given to him long ago by the Fánaí, a curious warhorn for summoning spirit totems. The gift had never called to him and he had not thought of it in years.

“A spirit totem reflects your soul, Topengorang,” urged the soul-catcher. “It encompasses you. A spirit totem is your circumference of being. You are bound within its territorial sphere, and it touches the world around you in ways deeper than you can imagine.”

“I have heard the Rhangorian Shamans speak of such things,” said Elandon, “but I am unsure of how one discovers his spirit totems.”

“They appear in times of need and offer protection, often in subtle and obscure ways. Yet the communion is tangible,” he smiled, bringing his hands to his chest. “You feel it here, in your heart.”

Just then a raven slowly flapped its wings across the sky overhead and cawed, looking directly down at them. Elandon realized his companion from the cave was following, for the timbre and pattern of the screeches, one followed by two, the second trailing off shorter than the first, were familiar. Once again, refracted light flashed from his witch-eye.

How large is a raven’s territory, Elandon?

After the brief rest they traveled on. Before them the swampy plain widened out and the jagged line of mountains comprising the Darkwall boundary lay in the distance, sleeping in a purple haze beneath the great clouds. As they crossed the marshland, Manuuwan spoke of his own spirit totems; one of these was the mighty bear he called Koda, whom was somewhere nearby, for occasionally its musky smell could be detected in the shifting breeze. Another was a red-bellied lemur he had raised from infancy. He had named the animal Tongo and stayed in touch with it through various vocalizations ranging from high pitched moans to soft humming calls. Manuuwan described how Tongo traveled both in the treetops and along the forest floor, keeping him informed about the patterns and behaviors of the surrounding jungle.

The soul-catcher possessed the subtle skill of guiding Elandon into an alternate state of awareness, ushering him through the vibrant and interrelated realities of the plant and animal kingdoms―those mostly hidden from the untrained eye, existences teeming with the enigmas of life. Calling them worlds within worlds as he adroitly invited each one into distinctive focus, Manuuwan explained this attuned sentience as ‘totemic attention,’ a sensual communion also known as Naguia.

“You must master Naguia before your soul can journey, Topengorang. Only then can you become one with your spirit totem and transform yourself to its dimension.”

“By that, do you mean actually shapeshifting into animal form?”

“Becoming one with your spirit totem,” Manuuwan explained, “is a dual expression of reality, a world within a world. But this cannot be known through words alone. It must be experienced. For now, simply invite this to occur in your mind.”

“Am I to become a sorcerer myself, then?” Elandon asked, his tone of voice betraying a measure of skepticism and impatience. Yet even as he heard the hollow echo of the words in his ears, a tingling sensation moved down his arms and into his fingertips, and a charge of excitement coursed through his spine. All at once, he found himself both envisioning and feeling the long narrow wings of the raven in flight, soaring high above the misty rainforest and into the indigo spires and crests of the distant mountains. Then he looked up and spied the black bird in the far away sky, realizing its position correlated with the perspective he experienced.

Once again Manuuwan laughed hardily. “What you shall become is a warrior of the boundary, a Bayang Penari. It means shadow dancer and involves the art of shapeshifting. It is the only way for you to survive the Na Jao.”

♦♦♦

A storm cropped up out of nowhere, a commonplace occurrence in the rainforest. Ragged clouds streamed down the mountainsides and rain could be tasted on the cooling wind. Mist rolled across the savanna as the pair finally ascended the forested slopes which they had set out for hours ago. The distance was deceiving in the fading light and it took longer than Elandon expected, yet they seemed to have made it just in time. Manuuwan led the way to a narrow opening in the hillside, a cleft in the rocks with overhanging trees that provided shelter from the wind and weather. The soul-catcher had pointed out other such refuges along the way.

The storm grew, splattering the first drops of rain upon them as they quickly gathered firewood. A bruise of violet and black stained the heavens and before long a steady rain poured from the dusky sky. As Elandon collected the last pieces of dead wood and separated out the kindling, Manuuwan used flint and brazzle to spark tiny shreds of bark into flames that soon became a glowing fire.

Up until that moment, Elandon had been in awe of the soul-catcher’s command of the common speech, the pronunciation, tone, nuance, vocabulary; all were extremely impressive for one who had adopted the language. In fact, Manuuwan appeared adept at learning languages, for he was also fluent in countless dialects of the jungle. Yet suddenly, that calm solicitous voice, and the words he spoke, evoked a feeling of dread. Despite the cold rain that now fell in stinging sheets, Elandon was wary of entering the shelter.

“I am ready, Topengorang,” he beckoned, “for you to tell me of your sorrow.”

Caught unprepared by the entreaty, Elandon was loath to respond. The gusts through the foothills swirled around him in an eerie twilight mist, seemingly boiling up from no place. The rising winds began howling among the escarpments, driving the rain even harder. “What sorrow would that be?”

“I think you know,” the soul-catcher said gently.

“And I think you comprehend a great many things which are impossible for one to know of another.” Elandon felt his wrath simmer like the mist surrounding him, and the winds wailed his defiance. He resented Manuuwan for presuming to help him exhume the long-dead bones of his past.

“Topengorang,” the tone was soft and lulling, like a mother’s crooning, “your healing cannot begin until we extract that which poisons your soul.”

“I am content the way I am,” he gasped, his breath coming hard now.

Manuuwan reached out his arms, inviting him to the fire. “No one is content with rage and grief. You have carried your burden long enough. The time has come for you to lay it down.”

Again the soul-catcher’s voice and manner seemed to compel a deeper recognition, in this instance stirring vestiges of the past which Elandon attempted to deny. The rain that soaked his mask suddenly felt like real tears. He dropped the stack of wood he was carrying and screamed out vehemently. “Burden though it may be, it is all I have left!”

The Mischanter silently arose and came out to regather the spilled firewood. With a tender smile and nod of his head, he said, “Come in from the rain, Topengorang. I will cook something for us to eat while we talk.”

With the fire burning brightly and warming the little hollow, Elandon soon realized his antipathy had been left outside in the wind and rain. He did not know where the soul-catcher found the small pot to hold the stew, or where the dried meat and vegetables and spices came from, or the cornmeal to make the bread. The prospect of hot food was especially appealing since he had been subsisting primarily on fruits and nuts, and as he watched Manuuwan prepare the meal and smelled the savory aromas as it cooked, his resistance dissolved.

Haltingly at first but then gaining momentum, he recounted the tale of the dark sisters insurrection twenty years before: their siege of Old Cathonia and the devastation and loss of innocent life wrought by his summoning of the fireclouds; the talismanic quarterstaff of the Paladins which he lost in the fallout; the valor of the Mother Superior and the warder who had rescued him; the long recovery from burns and a near fatal head wound that resulted in blindness; the fashioning of his mask from a spelled weave of fabric and the miraculous consecration of the crystalline witch-eye by the Sorers; regaining his strength by training with the bonded warders and battle matrons at Cape Caule; and finally, his almost two decades of wielding the glowing sword―the revenant of King Harek given to him by the Fánaí, while losing himself in championing the resistance to the Shadowkind across the Lar Isles. Indeed, he told Manuuwan all of it, bearing his soul like never before, and in the end he wept.

♦♦♦

Elandon raised his head and looked out into the foothills, where evening had fallen. The storm had passed and stars shone brightly across the sky. The fresh scents in the air were intensified, the shrubs and ferns, the leaves and damp bark of the trees, the pungent odor of the humus covering the forest floor. Rising from the marshlands below, the lone screech of a night bird pieced the darkness.

“Now you know of my sorrow,” said Elandon. He removed the sword from across his back and withdrew it from the scabbard, turning it this way and that before the fire. Tracing his fingers across the engraving on the luminous blade just below the hilt, as he had countless times before, he read the familiar inscriptions by touch, first one side and then the other.

Hold No Blackness . . . In Thy Heart.

He had failed to live up to the cryptic legend. Yet at this moment, as he re-sheathed the weapon, he experienced a distinct sense of liberation. For the first time he felt equal to his long-standing adversaries: despair and remorse.

The little fire Manuuwan built still burned, the pot bubbled, and the corn cakes were now baked. The soul-catcher sat and watched him, his face serene and yet somber. “Sorrow is not what poisons your soul, Topengorang. Participating in life’s inevitable sorrows is an affirmation of living. It is a measure of your true character.”

“What is the poison, then?” Elandon demanded. “I wish to know this blackness, that I may vanquish it.”

“Shame,” Manuuwan said, softly. “Shame is your keeper. When you were called to save Old Cathonia, how many turns were there for you, on the great wheel in the sky?”

“I had celebrated the solstice of fifteen summers,” said Elandon.

“I see,” Manuuwan nodded, ladling stew into a wooden bowl and offering it to Elandon. He then picked up one of the corn cakes he had made and handed it over. “Let us eat now and then you will feel better.”

They ate together in silence and the meal tasted even better than it smelled. Elandon sopped the rich broth with a second cake and savored the last few bites. The food in his stomach and the warmth of the shelter made him drowsy. He set his bowl aside and lay back, drawing his cloak loosely around himself. A chill breeze had blown in behind the storm and the night promised to be cool.

“Sleep now, Topengorang,” soothed the soul-catcher. “Sleep well. We shall talk more of it tomorrow.”

♦♦♦

Tongo had awakened them with plums for breakfast. The furry, chestnut colored lemur with distinctive white markings beneath its eyes was decidedly amiable and readily shared affections with the soul-catcher, but had been cautious around Elandon, keeping its distance while sniffing and appraising the masked stranger dressed in leathers. Now, the agile little creature scurried ahead into the hills and beckoned for them to follow.

The sun climbed the sky as they navigated the uplands. Stark outcroppings of rock loomed before them and small trees, bent and twisted, weathered a stunted existence among the boulders and scree. Below were narrow valleys with magnificent waterfalls, flowering fields, and verdant knolls and braes that vibrated with color as the updrafts dispersed the morning mists into sunlight. Above them, ferns walled the forest at the tree line.

Leading the way across winding ridges to the crest of a hazy vale, Tongo turned and plunged down through the thicket and into the forest, where he disappeared. They found him some time later in a flourishing grove of white blossomed plum trees, pervaded by an atmosphere of pollen-infused indolence. What waited there broke the charm of the morning and shocked even the battle hardened Elandon, for in the ground among the fallen blooms, soaking face up in a bladder-lined pit filled with a frothy green liquid, was a recently severed head.

Tongo scampered about mewing and purling at the soul-catcher, who knelt and carefully examined the contents of the pit. “This is what I brought from Mission’s Cross. It will serve to reinforce the spells that bind Darkwall.”

“I’m afraid I don’t understand.”

Manuuwan’s smile was neither woeful nor joyous, but rather the slim, mysterious grin of one with a secret he wishes to share. “Soon enough you will know, Topengorang. But first, you must come to embrace death as more than a corpse, or even a husk. Do you know who this is?”

The slender contour and marked Rhangorian features were in fact vaguely familiar, but Elandon was perplexed by the gruesome sight and couldn’t quite identify the face. Then, as the soul-catcher spoke, the truth dawned on him.

“Look at the eyes,” said Manuuwan.

Memories flooded his awareness as Elandon realized it was the severed head of the Cathonian prophet, Davada Cruz, whose eyes of crimson stared piercingly up at him. Stunned into silence, he could only nod in recognition.

From his leather pouch the soul-catcher removed bamboo shoots, seeds, and knotty roots, which he pressed between rocks to extract scant drops of milky juice. These were then ground with the seeds and fungi powders from the shoots to form a virid, pasty mixture. As he carefully stirred the concoction into the liquid inside the pit, the broth gurgled and foamed as an oily sheen spread across the surface. Manuuwan stood and studied the volatile brew until he was satisfied; then he covered the pit with swatches of moss and white plum blossoms.

“I minister the last and greatest sacrifice of the sacred flesh,” he said, speaking barely above a whisper, “the consummation of all the sacrifices that have come before. I must not fail the teachings.”

The words filled Elandon with foreboding. The Second Sight stirred within him but the voice offered little reassurance.

Answers are questions, Elandon.

Seemingly reading the prismatic glints of light from his witch-eye, Manuuwan gestured as he casually began to pick plums and place them into a cloth sack that had appeared from nowhere. “Come now,” he said, “tell me of your misgivings.”

“The duality of the Prophecy of the Sacred Flesh is notorious,” Elandon chided, recalling the prophet’s teachings for himself. “This reeks of the dark sisters and their black sorcery.”

Manuuwan smiled. “Your suspicions are well founded, but you must allow them to be allayed. While many realize the prophecy originated in the Na Jao jungle, few comprehend how that came to be. One must surrender to both worlds, the living and the dead, to witness the truth of it.”

“Where is the rest of his body?”

“Packed in salt at Mission’s Cross,” said the soul-catcher. “It is in the safe hands of the Sorers. The white witches sent me to find you, Topengorang. Your quest to pass through the Darkwall boundary was foreseen by the prophet.”

♦♦♦

The journey with the soul-catcher began to change Elandon. What he had seen and knew of death and evil and even sorcery itself, was being cast into a new light. The days that followed were enlivening and adventurous, for Manuuwan was an expert with the blowgun and they hunted and fished and told each other stories in the evenings. Tongo was keen at detecting the squalls that blew up and when the thrumming rains grew into roaring storms and rendered the slopes treacherous, he would lead them to shelter in the galleries of the forest. Slowly, they trekked westward across the ancient switchbacks into the gelap dinding, the Darkwall boundary, wending their way upward through sweeping cloud banks pierced by rainbow arcs and drifts of blue and red-winged butterflies. Still, their plight was not carefree and at times Elandon sensed that all the terror in the world lay between him and the curious Mischanter.

By the fourth day they had climbed the northern massif of the boundary, a rugged region known as the Angavo Cliff. The weather at this elevation was cooler, especially after sundown, and they huddled by the fire eating freshly caught trout and tubers roasted together in banana leaves. Manuuwan wore a boar’s hide mantle, which had been stored in a cleverly sewn bag of oiled leather in one of the refuges they passed along way. Elandon now realized the soul-catcher had caches in these strategically located shelters.

“Is Mission’s Cross where you learned the common speech?” he inquired, as they finished the meal.

“I perfected the language there,” replied Manuuwan. “But the Mages of Awen brought the common speech to the people long ago, for it was they who gave the name ‘Darkwall’ to the gelap dinding and christened the holy men of the tribes as ‘Mischanters.’ Many of our people have schooled with the witches at Mission’s Cross, though, for their gift of the enuncio is a profound vessel of translation. I’m sure you know of it?”

“The enuncio is a form of clairvoyance, a sway of vocal intonation that is both suggestive and interpretative. The witches use it in many ways. In certain instances one must guard against its influence.”

“Indeed,” agreed the soul-catcher, “though I must say I was never aware of the Sorers abusing the gift. They were great and patient teachers.”

“The Sorers at the Cathonian Missions have taught the people of the Lar Isles to read and write,” stated Elandon. “They also tend the sick and the needy and are some of the most altruistic individuals one could ever know. Unfortunately, the same is not true of their dark sisters, the Adelphi Priestesses, or the Sisterhood as a whole.”

Manuuwan broke into his sly grin. “Just like the Rhangorian Shamans, the witches are intrigued by the Mischanters. You know something of that, I imagine.”

“Do we speak of Haedeus, the Mischanter priest of the dark sisters?”

“We shall, Topengorang. Of course, you realize he came from the Na Jao tribes. Their ways are not the ways of the Ungorath people. There is also the matter of the fallen mage, the one called Maershyl. His tale and that of Haedeus are inexorably intertwined.”

“The histories of the Sea Kings refer to him as Maershyl the traitor,” offered Elandon, “and he was among the mages who originally explored and raised the Darkwall boundary. He was later banished by the Mages of Awen for practicing black sorcery. Rather than face a tribunal for his transgressions, he fled and was rumored to have ended up in the Na Jao jungle.”

“It is not a rumor,” asserted Manuuwan. “Tribal lore recalls that the fallen mage coveted the powerful talisman used to uplift and fashion the eastern and western scarps of the boundary into impassable overhangs above the coastal plains. What can you tell me of that, Topengorang?”

“The talisman is called the Wind Pentacle. It is the most powerful of five such talismans of elemental magic created by the Mages of Awen when the Sea Kings first settled the Lar Isles. The one I lost in Old Cathonia, the Sky Pentacle, is a lesser talisman of the set which together are called the Star Cross Pentacles. Maershyl had a major hand in forging and consecrating them and believed he was best suited to wield the mighty Wind Pentacle, but the High Mage of the Awen and the Sea Kings disagreed. Thus began his dissension with the Order.”

Manuuwan contemplated this for a few moments. “It is an interesting tale,” he sighed, “and a great deal more than I could ever exact from the witches at Mission’s Cross, for the fate of the fallen mage is a taboo subject with them. But at least for now, it does not shed much light on things. Where is this Wind Pentacle now?”

“Locked away in the castle of Rimlock,” replied Elandon, “in Rhangoria. Alas, all of the lesser pentacles, those of water, fire, earth . . . and sky, have been lost through the ages.”

“I fear the worst about that, somehow,” averred the soul-catcher. “You should know that after all this time Maershyl still lives in the Na Jao. He is the ‘Terrible Spirit,’ the Puta Hantu, as the people call him.”

“I don’t see how that can be,” Elandon said, doubtfully. “His time dates back more than a thousand years.”

“You shall discover it for yourself. This is why you have come to the Darkwall boundary, to the heart of darkness, is it not? But first, you must experience the visions of the serpent, which will show you the path to follow.”

Elandon’s voice was quiet and assured. “I am ready.”

“Good, Topengorang! Tomorrow you face the bushmaster.”

♦♦♦

Elandon slept fitfully that night and was haunted by strange and discordant dreams, yet he awoke feeling rested. The morning found them once again traversing the ridgelines at the top of the world, where the great trees knelt before granite buttresses and rising stone peaks. It was a time of quiet reflection upon the journey that had led to the rugged trails of the Angavo Cliff.

Although he still did not have a clear idea of when or how they would pass through the Darkwall boundary, his gamble that a Mischanter or boundary warrior would come to guide him had paid off. Manuuwan was proving to be an affable companion and the physical exertion and resplendent beauty of the terrain assuaged his restlessness. Still a certain unease lingered, as the previous night’s dreams were not the first to include the conflicted visage of the plum grove and the prophet’s severed head in a pit of fuming muck, crimson eyes staring up at him.

Sometime near midday Tongo emerged through a fern break above a tiny stream and motioned them closer. When they approached, the soul-catcher put his hand on Elandon’s shoulder and pointed his blowgun at a narrow fissure in the rocks, an opening barely larger than a man’s head.

“There is the lair. You must reach inside, Topengorang.”

Elandon hesitated. “Am I to be bitten of my own volition?” he said, tentatively.

“Offering oneself is the first test of fate for a Bayang Penari. You will surely be bitten, and the effects of countering the poison will cause you to hallucinate. This is the first vision of the serpent. At this elevation, the bushmaster’s venom is not as potent. But still, if the boundary deems you insincere, or your powers unworthy, you may die.”

“How many are in there?”

“Perhaps twenty,” answered Manuuwan.

The lines of the soul-catcher’s face took on a knife-edged countenance and he spread his arms wide. “A Bayang Penari knows fear as the living death of the world. He never ignores it. And with this knowledge, he understands how to draw forth fear from others. This is why the boundary warriors are welcome in any tribe or village across Dramhail. Indeed, it is easier to face the Horks and Trolls than it is the serpent, which is why you must conquer your instinctive fear and reach inside the lair.”

Learn the dance of the shadow, Elandon.

The Second Sight quickened inside of him. Clarity of perception, the voice of inner knowing which had become muddled through his years of despair and remorse, was somehow renewed in this defining moment. A greater truth was revealed as he acknowledged his fear of the viper den.

“The lair of the bushmaster symbolizes something in life which must be overcome in order to be a boundary warrior. What is that for you, Topengorang?”

“Shame,” Elandon replied, without hesitation. He removed the gauntlet from his left hand and tucked it in his belt.

“Then you are ready. Remember that Naguia is the same for all living creatures. The lair of the bushmaster is a world within a world. Become one with it.” Manuuwan then stepped back and Tongo settled onto an overhanging tree branch, his white tear-dropped eyes looking down inquisitively.

Flashes glistered from Elandon’s witch-eye as he approached the opening in the rocks and focused inside the nest of coiled snakes. An unfamiliar dynamic began to occur as his uncanny ability to see catalyzed with the newly learned facility of totemic attention, creating a crystalline force of vision he had never before experienced. Indeed, with each deep, measured breath he took everything in his periphery of sight slowed down. He reached in and as one of the vipers struck he quickly snapped back his hand. An uncharacteristic look of bafflement came over Manuuwan’s face as twice more this transpired, with Elandon’s reflexive reactions being too swift for the snakes inside the lair. Yet what only Tongo saw from above―for the lemur screeched in warning, was that a bushmaster just returning to the den had slithered into position to deliver a blindsided strike.

Elandon detected the motion at the last instant and whipped around, but it was too late. Fang marks formed a stinging red welt in the skin between the thumb and forefinger of his hand. The flesh immediately began to swell and pain shot up his arm. In a keen, after the fact insight that came to him even as he swooned, Elandon realized the viper that bit him had been in his range of sight, but he had been too intent on the lair itself and was preoccupied with how intensely the Naguia had enhanced his perceptions and abilities.

With a razor sharp bone knife extracted from his leather pouch, Manuuwan took Elandon’s hand and made deep incisions on either side of the snake bite. He produced a stretchy fish bladder and put it to his lips, inhaling to create suction as he pressed the vessel firmly over the incisions and drew forth spurts of blood. Even as Elandon felt the numbing sensation spreading through his body, the Mischanter smiled and spoke.

“I have drawn out most of the venom, Topengorang.”

Elandon’s witch-eye clouded and his breathing became labored. “I can feel it,” he said, the words slurred and barely audible, “moving to my heart.”

He salivated as Manuuwan gently forced bits of crushed leaves, herbs, and bitter tasting lichen into his mouth. “Stay awake and you will not die,” said the Mischanter, calmly. “I will catch your soul.”

♦♦♦

The trails of buzzing black flies and wasps streamed across the slanted sky. Wind drummed through the trees like rain. The pain in Elandon’s left hand was gone; he felt nothing in his arm and very little if anything of his body. Watching the breezes swirling through the fern fronds, it occurred to him that if the venom of the bushmaster killed him, his shame would surely be vanquished. At the same time, the realization came that he had felt no despondency or self-reproach―or fear, for that matter, since the viper seized his hand. In fact, he was breathing easier and his vision was clearing. All about him the air flickered with opalescent light from the crystalline orb that granted him sight.

Manuuwan and Tongo had not been gone long. They returned carrying bunches of bananas and the soul-catcher held a net with a number of large, reddish striped spiders. By their color and markings, Elandon recognized them as banana spiders, a species whose extremely poisonous venom also possessed healing qualities. In an efficient and well-rehearsed manner, Manuuwan peeled bananas and broke them into small chunks, which Tongo speared with the sharp fingernail on the first digit of each hand. The lemur then reached into the net and deftly teased and agitated the aggressive arachnids into frenzied attacks, causing them to envenomate the pieces of fruit. Tongo came over and fed each piece to Elandon, one after the other, until he had consumed almost two bananas.

It was perhaps an hour before the venoms of the spider and the serpent interacted. The surrounding landscape gradually splintered into slivered rainbows and the vision began. Elandon found himself rising and stepping away from the fleshly confines of his body, a young boy of perhaps eight years. In many ways he was just as he remembered being, but his ethereal presence was breaking up, scattering and regathering like reflections in a pool of water. He could see himself with the witch-eye, the dual realities of his poisoned flesh on the threshold of death, and his exalted soul, vibrant and alive and filled with child-like awe and wonder. It was the polarity of darkness and light—both together and separate, the enigma of the Spirit he recognized as the old magic of creation.

“Come,” said Manuuwan, offering his hand. The soul-catcher’s touch was the thrill of a thundering waterfall. “We shall help the aura of your spirit child grow stronger.”

The boy stepped forward into a vaporous white light. “Where are we?” he asked.

“We are between the worlds of the living and the dead, a place the Mischanters call the medicine cloud. The sky has come down to save you.”

Barely visible was a motif of glassine colors akin to the western shores of Rhangoria where he had grown up. The more he concentrated, the clearer the scene became; the steep fiord and famous bridge across it, connecting the castles of Rimlock and Stonehaven which were his home. Stars shone in a sky cascading with emerald light from the auroras, the most stunning twilight he had ever seen. He attempted to pull away but Manuuwan gripped his hand tightly.

“You are not ready to go there,” said the soul-catcher. “It is the place of the dead. You must remain here in the medicine cloud, between worlds.”

A figure had appeared from the walls of Rimlock, a tall, broad shouldered man that Elandon immediately recognized. “That is my father,” he exclaimed. Another figure then stepped down from the tracery of the brilliant sky, this one a magnificent black wolf with piercing yellow eyes; together the two strode out onto the great bridge between the castles.

“They have come to give you power in your quest as a warrior and champion.”

Be true to your birthright, my son. Trust your charge to summon the ancient guardians. Heed the gift of crystalline vision.

A resounding clarity rang through Elandon, as if the world of the living was a bell that beckoned his return. The dazzling vision of Rhangoria melted away, along with the core of anguish and regret he had carried for nearly two decades. That burden did not belong to the spirit child who entered the medicine cloud, or to the one who emerged from it changed forever. Elandon was drawn back into his limp body and though the toxins were still present, the feeling of being divinely rejoined with his soul prevailed. A vital part of himself had been reclaimed.

“You belong to life again, Topengorang, not to death.”

Ribbons of prismatic light reflected from his witch-eye. Alchemic marvel though it was, he had never quite regarded the crystal orb as a gift. Yet his father had referred to it as such: Heed the gift of crystalline vision. The cataract of shame blurring his perceptions had been razed. Elandon looked up through the trees and into the surrounding mountains. He saw the fragile and reckless order of all things. As never before, he beheld the loamy clouds that soothed the sky―a sky that reflected not just his sorrows, but the sorrows of the world.

“You are becoming a Bayang Penari,” said the soul-catcher, “a shadow dancer.”

♦♦♦

The following days were spent drinking copious amounts of water to flush the toxins from his body. Manuuwan built a shelter for them, a lean-to of interwoven tree branches lashed together with cunningly knotted lengths of hemp and anchored by guylines staked in the ground. It not only kept them dry from the intermittent rains but proved strong enough to withstand the gusting mountain winds. In his clear-headed moments, Elandon studied the resourceful construction and had the soul-catcher show him the clever knots, which he practiced as a kind of therapy to coax the feeling back into his left hand and arm.

They stayed by the stream at the crest of the Angavo Cliff until his fever passed. Lying on his back as chills gave way to dewy beads of sweat across his skin, Elandon meditated upon the weather patterns through his lens of crystalline vision, the shifting winds and sudden storms and surges of rising mists from the forest below, shredding and thinning away. The surreal visage of the medicine cloud would periodically return, his homeland of Rhangoria witnessed through the eyes of his auric spirit child, his father’s loving and poignant words of wisdom, the legendary black wolf―an ancient guardian that struck fear into the hearts of man and demon alike; and so it was, as the sense of being reborn to himself and his heritage deepened, he came to understand more of what Manuuwan had meant by the sky coming down to save him.

The renewed clarity of his Second Sight and the phenomenon of Naguia also occupied Elandon’s consciousness, the latter due especially to the frequent visits of the raven bringing him grapes and berries. He had taken to calling it Renyo, for during one of his feverish moments the black bird had spoken its name and startled him into alertness; and although such a thing seemed unfeasible even to Elandon, he was certain of the fact. When he told Manuuwan of this, the soul-catcher smiled his sly smile.

“Renyo is a spirit totem, Topengorang. But of course you already knew that.”

“Still, it’s extraordinary for a raven to talk, is it not?”

“All language, every dialect, comes from the landscape of shadowed voices,” said the soul-catcher. “All of it speaks, the feathered bodies, the fur and fangs and claws, the caterwauls beneath the moon, the antlers quietly gathered by tumbling streams, all the beings with whom we are engaged and share existence, with whom we struggle and suffer and celebrate.”

Elandon’s witch-eye flashed. “Naguia works both ways.”

“Especially in the realm of spirit totems,” he nodded. “Ravens are seen in the rainforest from time to time but it is not their natural habitat. Renyo has followed you here.”

“How can you be certain of that?”

“Because,” laughed Manuuwan, “he speaks to me too.”

“Is there more to know of it, then?”

“Much more,” replied the soul-catcher, choosing his words carefully. “Most of it you must discover for yourself. But I will tell you that Renyo shares your bounding with another totem, a mighty and fabled creature that dwells in the Cairn Mountains of Saorsa. This one leads a great kin that awaits your return.”

Perhaps there is truth in the ancient folk myths of the wolves?

The connection was instantaneous. “Then I shall share the spirit totems of a wolf and a raven.”

“So it would seem.”

“The revelations of the medicine cloud are still unfolding,” he mused.

“And they will continue to do so,” said Manuuwan, “even after the malaise passes.”

His fever broke that night and the next day the boundary warriors, Yano and Javari, arrived with the severed head of the prophet, resting inside a cauldron they carried. They were attired much like Manuuwan, wearing knee-length waistcloths with their legs tattooed by twining serpents, yet their eyelids and torsos were free of the intricate patterns of woad that designated a Mischanter. They carried spears and blowguns and were not nearly as fluent in the common speech, yet both possessed enough of the language to be understood and congratulated Elandon on having passed the first test of the Bayang Penari.

He stood aside and watched as the two warriors removed the preserved head from its protective bladder. The pale skin glistened in the sunlight and bloodless strings of flesh dangled from the hewn neck. The fuming solution Manuuwan had prepared had softened the skull and now the two warriors scooped out the soggy insides, bone and brains alike, being careful to set aside the curiously unaltered crimson eyes. Meanwhile, the soul-catcher stoked the fire and collected water and sand from the stream inside the cauldron, which he heated to a boil. When it was ready, he flattened the deboned head like a hide and tied its tattered strings to the inner branch of a tree, near the bough. He delicately filled the inverted head-husk with sizzling hot sand and it slowly took on the physical aspects of a living man. With a bone needle and fine filament he skillfully stitched the crimson eyes―which still held their mantic stare―into place. Manuuwan swung the head upright and balanced it at an angle between the bough and inner branches so the sand trickled from the neck. After several hours the flesh had shrunk as the sand cooled and leaked away, and he repeated the process. Over the next two days the head of Davada Cruz was shrunken down to the size of a man’s fist.

The amulet that would reinforce the spells of the Darkwall boundary was ready. The barbaric process, which was both disturbing and fascinating and had tested Elandon’s trust in the soul-catcher, somehow served to reinforce that trust in the end. Manuuwan was his guide, his teacher, his friend, and because of his wisdom, Elandon was rising not just to the challenge of the jungle’s matchless sorcery but to horizons beyond, where his ultimate destiny awaited.

As the after-effects of the venoms passed and his health returned, he had also become aware that his sense of urgency and restlessness had subsided. Elandon thought maybe this too had evaporated with the medicine cloud, or perhaps it was an instinctive reaction to preserve his new found sense of redemption. In any case, as he pondered the macabre amulet it dawned on him that thus far his burgeoning gift of crystalline vision had merely granted insights into his own existence, as opposed to those of an oracular or prophetic nature. Lifetimes of despair and disaffection shown in the haunting eyes of Davada Cruz―eyes that still appeared filled with life―and he distinguished the difference between perceiving one’s own fate and that of divining the fates of others and the world.

Be grateful for what you cannot see, Elandon.

♦♦♦

Copyright © Shawn Quinlivan, 2018. Shawn Quinlivan asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work. All original images used by permission. Digital artistry by Shawn Quinlivan.